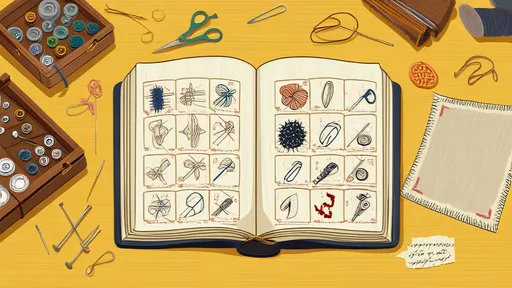

The art of hand-stitched hemming, once a cornerstone of textile craftsmanship, now teeters on the brink of obscurity. Among the countless techniques developed over centuries, twenty-three distinct hemming methods face imminent extinction. These intricate approaches to fabric finishing, each with unique structural and aesthetic qualities, represent vanishing chapters in the story of human ingenuity with needle and thread.

In the quiet corners of tailoring ateliers and the workrooms of elderly seamstresses, fragments of these endangered techniques persist. The Bridesburg Blind Stitch, for instance, creates an invisible fold so precise it appears machine-made, yet possesses a durability no industrial method can replicate. Its cousin, the Marseilles Twist, employs an unusual counter-thread tension that allows linen to drape without puckering—a solution developed by 18th-century sailmakers adapting to humid Mediterranean winds.

What makes these disappearing methods extraordinary isn't merely their technical execution, but the cultural narratives woven into their creation. The Kyoto Mountain Hem, developed by Japanese kimono artisans, incorporates irregular stitching intervals that mimic falling cherry blossoms when viewed from specific angles. Similarly, the Baltic Ice Stitch—developed by Scandinavian fisherwomen—uses waxed thread in geometric patterns that shed water like a duck's plumage.

The industrialization of textile production rendered many techniques commercially impractical. A single yard of Venetian Lattice Hem, requiring eighteen passes of alternating silk and metallic threads, might consume a week's labor. Yet modern manufacturers fail to replicate how this method prevents fraying in delicate brocades while maintaining perfect drape. The Alexandria Cross-Knot, developed for ancient Egyptian burial linens, actually tightens its grip on fabric fibers with each washing—a property modern science still cannot satisfactorily explain.

Contemporary fast fashion's emphasis on speed over quality accelerated this cultural erosion. Where apprentices once spent years mastering the Vienna Concert Hem (so named because its inventor claimed the stitch rhythm matched Mozart's symphonies), today's garment workers learn standardized techniques in weeks. The Madras Check Lock, developed to secure India's famous plaid cottons without adding bulk, now survives in only three documented practitioners worldwide.

Material science reveals why these antique methods outperform modern shortcuts. Microscopic analysis shows how the Glasgow Industrial Hem from 19th-century Scotland creates microscopic fiber loops that distribute stress evenly, preventing the "zipper effect" that causes machine-sewn seams to fail catastrophically. Similarly, the Andean Over-Under Stitch, developed by Inca weavers, incorporates alpaca wool's natural scales in a way that makes seams actually strengthen with friction—perfect for mountainous terrain.

Revival efforts face significant hurdles. The Lisbon Wave Stitch requires simultaneous tension from both hands and teeth—a technique modern health regulations prohibit in commercial settings. Other methods, like the Persian Garden Hem, depend on thread spun from discontinued silk varieties. Most tragically, the Hanoi Basket Weave exists only in partial documentation after its last master died mid-stitch during the Vietnam War, leaving her final demonstration sample incomplete.

Digital archivists race against time, using spectral imaging to reconstruct techniques from antique textiles. A 2023 study of 16th-century Flemish tapestries revealed the Antwerp Cathedral Join—a method previously assumed impossible until imaging showed how craftsmen used hollow needles to hide structural knots inside individual threads. Meanwhile, the Bombay Invisible Lock was recently rediscovered in the marginalia of a Portuguese trader's 1612 diary, describing a technique Indian tailors used to secure gold threads without visible anchoring.

Economic realities complicate preservation. A single hand-stitched sleeve using the Savile Row Whisper Stitch (which eliminates lapel roll in woolens) costs more than an entire mass-produced suit. Yet luxury brands quietly incorporate these heritage techniques—a Hermès scarf's hand-rolled edges employ a simplified Biarritz Shell Hem, while certain Italian shoemakers still use the Florentine Triple Pass for invisible sole stitching.

The most heartbreaking losses may be techniques serving specialized functions we no longer recognize. The Constantinople Fire Stitch, designed to slow flame spread in theater curtains, used asbestos-free mineral threads in a pattern that created insulating air pockets. The Manila Rope Bind, developed for sailing ships, could withstand years of saltwater exposure yet unravel with one strategic tug—critical for quick sail adjustments in storms.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy lies in how these techniques represent lost cognitive traditions. Mastering the Celtic Maze Hem required visualizing seven intersecting stitch paths simultaneously—a mental map modern brain scans show activates both mathematical and artistic neural networks unusually. Similarly, the Samarkand Echo Stitch involved counting thread crossings not numerically, but through a rhythmic tapping system resembling Morse code.

As museums scramble to document these techniques, ethical questions emerge. Should the Vienna Concert Hem be preserved through motion-capture technology that records a surviving practitioner's muscle movements? Can the Kyoto Mountain Hem be patented if reconstructed from museum pieces? Meanwhile, indigenous communities rightfully demand control over techniques like the Navajo Nightway Lock, traditionally taught only during sacred ceremonies.

The race to preserve these twenty-three hemming methods represents more than textile conservation—it's safeguarding alternative relationships between hands, materials, and problem-solving. In an age of 3D-printed fabrics and self-repairing nanomaterials, these endangered stitches remind us that elegance often lies not in high-tech solutions, but in centuries of accumulated wisdom passing quietly into history's folded edges.

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025